37 Constitutional Constraints

Contemporary defamation law has evolved to include substantial constitutional limits on the interests protected through the tort. At a pivotal moment in the Civil Rights Movement in 1964, the Supreme Court handed down a landmark decision, New York Times v. Sullivan, in which it ruled that Alabama’s libel law unconstitutionally infringed on the First Amendment’s protections for freedom of speech. New York Times v. Sullivan fundamentally altered the legal landscape. Sullivan’s importance is hard to overstate. If you’ve worked in journalism or studied mass media or communications, you likely have lived with or studied its impact. It marks a critical moment when advocates succeeded in using the judicial system to expand journalists’ capacity to report on civil rights violations, and it fundamentally changed the law of all U.S. jurisdictions with respect to defamation. By defining parameters within which the First Amendment trumped the rights of states to protect individuals’ reputational interests, it “constitutionalized” state law essentially overnight.

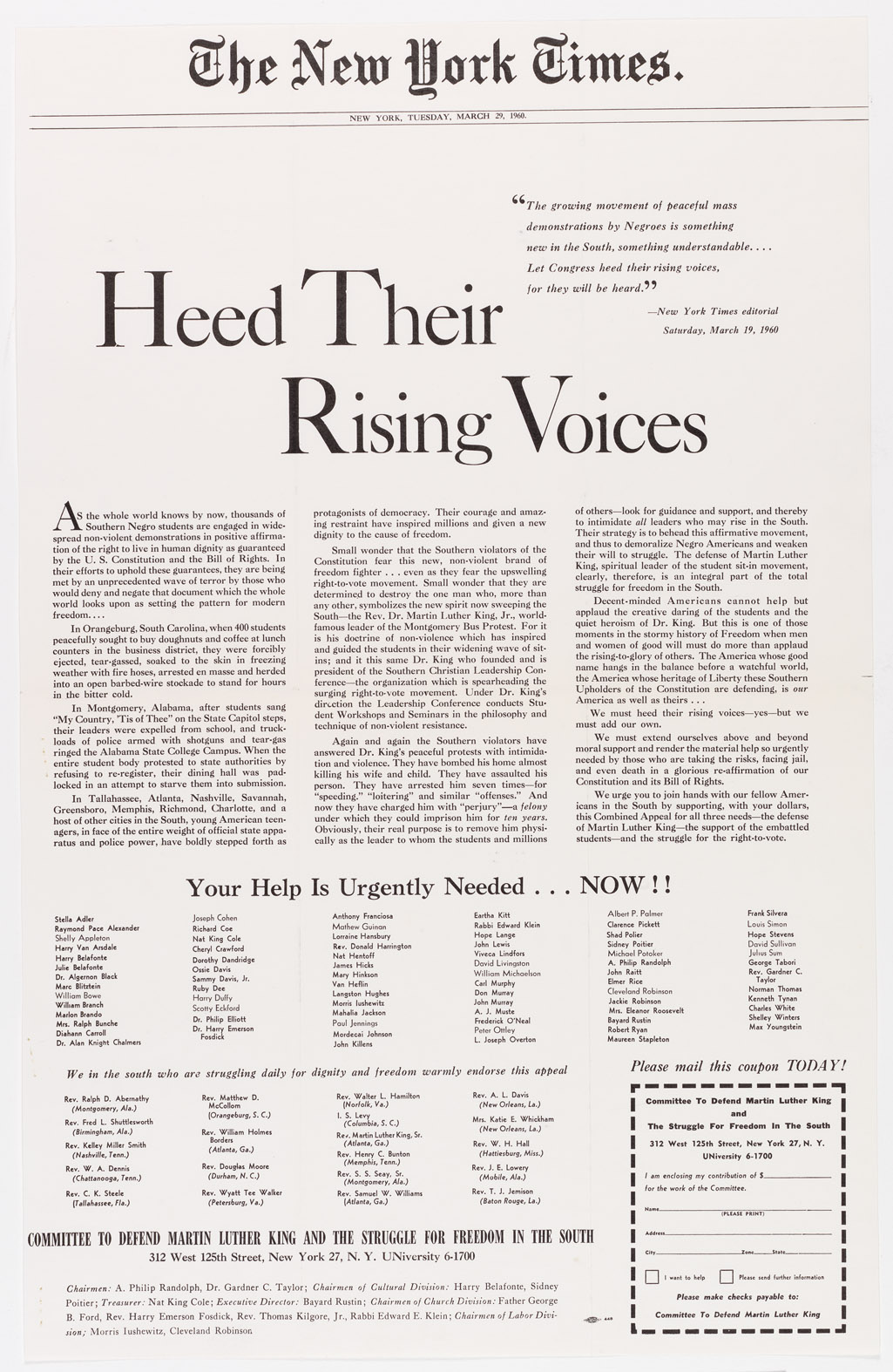

“Heed Their Rising Voices,” the advertisement at issue in Sullivan is reproduced below the opinion. The advertisement originally took up two full pages of the newspaper and was included as an appendix to the legal opinion.

Of further note: without intending anything derogatory or offensive, the opinion repeatedly uses the word “Negro.” This was deemed a respectful term at the time but is no longer so. Please use appropriate contemporary language unless quoting verbatim from the text. (Alternatively, please follow any class agreements or ground rules your instructor has set on the topic).

N.Y. Times v. Sullivan, Supreme Court of the United States (1964)

(84 S. Ct. 710)

Mr. Justice BRENNAN delivered the opinion of the Court.

We are required in this case to determine for the first time the extent to which the constitutional protections for speech and press limit a State’s power to award damages in a libel action brought by a public official against critics of his official conduct.

Respondent L. B. Sullivan is one of the three elected Commissioners of the City of Montgomery, Alabama. He testified that he was ‘Commissioner of Public Affairs and the duties are supervision of the Police Department, Fire Department, Department of Cemetery and Department of Scales’ He brought this civil libel action against the four individual petitioners, who are Negroes and Alabama clergymen, and against petitioner the New York Times Company, a New York corporation which publishes the New York Times, a daily newspaper. A jury in the Circuit Court of Montgomery County awarded him damages of $500,000, the full amount claimed, against all the petitioners, and the Supreme Court of Alabama affirmed. 273 Ala. 656, 144 So.2d 25.

Respondent’s complaint alleged that he had been libeled by statements in a full-page advertisement that was carried in the New York Times on March 29, 1960. Entitled ‘Heed Their Rising Voices,’ the advertisement began by stating that ‘As the whole world knows by now, thousands of Southern Negro students are engaged in widespread non-violent demonstrations in positive affirmation of the right to live in human dignity as guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights.’ It went on to charge that ‘in their efforts to uphold these guarantees, they are being met by an unprecedented wave of terror by those who would deny and negate that document which the whole world looks upon as setting the pattern for modern freedom. * * *’ Succeeding paragraphs purported to illustrate the ‘wave of terror’ by describing certain alleged events. The text concluded with an appeal for funds for three purposes: support of the student movement, ‘the struggle for the right-to-vote.’ and the legal defense of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., leader of the movement, against a perjury indictment then pending in Montgomery.

The text appeared over the names of 64 persons, many widely known for their *714 activities in public affairs, religion, trade unions, and the performing arts. Below these names, and under a line reading ‘We in the south who are struggling daily for dignity and freedom warmly endorse this appeal,’ appeared the names of the four individual petitioners and of 16 other persons, all but two of whom were identified as clergymen in various Southern cities. The advertisement was signed at the bottom of the page by the ‘Committee to Defend Martin Luther King and the Struggle for Freedom in the South,’ and the officers of the Committee were listed.

Of the 10 paragraphs of text in the advertisement, the third and a portion of the sixth were the basis of respondent’s claim of libel. They read as follows:

Third paragraph: ‘In Montgomery, Alabama, after students sang ‘My Country, ‘Tis of Thee’ on the State Capitol steps, their leaders were expelled from school, and truckloads of police armed with shotguns and tear-gas ringed the Alabama State College Campus. When the entire student body protested to state authorities by refusing to re-register, their dining hall was padlocked in an attempt to starve them into submission.’

Sixth paragraph: ‘Again and again the Southern violators have answered Dr. King’s peaceful protests with intimidation and violence. They have bombed his home almost killing his wife and child. They have assaulted his person. They have arrested him seven times—for ‘speeding,’ ‘loitering’ and similar ‘offenses.’ And now they have charged him with ‘perjury’—a felony under which they could imprison him for ten years. * * *’

Although neither of these statements mentions respondent by name, he contended that the word ‘police’ in the third paragraph referred to him as the Montgomery Commissioner who supervised the Police Department, so that he was being accused of ‘ringing’ the campus with police. He further claimed that the paragraph would be read as imputing to the police, and hence to him, the padlocking of the dining hall in order to starve the students into submission.[1] As to the sixth paragraph, he contended that since arrests are ordinarily made by the police, the statement ‘They have arrested (Dr. King) seven times’ would be read as referring to him; he further contended that the ‘They’ who did the arresting would be equated with the ‘They’ who committed the other described acts and with the ‘Southern violators.’ Thus, he argued, the paragraph would be read as accusing the Montgomery police, and hence him, of answering Dr. King’s protests with ‘intimidation and violence,’ bombing his home, assaulting his person, and charging him with perjury. Respondent and six other Montgomery residents testified that they read some or all of the statements as referring to him in his capacity as Commissioner.

It is uncontroverted that some of the statements contained in the two paragraphs were not accurate descriptions of events which occurred in Montgomery. Although Negro students staged a demonstration on the State Capital steps, they sang the National Anthem and not ‘My Country, ‘Tis of Thee.’ Although nine students were expelled by the State Board of Education, this was not for leading the demonstration at the Capitol, but for demanding service at a lunch counter in the Montgomery County Courthouse on another day. Not the entire student body, but most of it, had protested the expulsion, not by refusing to register, but by boycotting classes on *715 a single day; virtually all the students did register for the ensuing semester. The campus dining hall was not padlocked on any occasion, and the only students who may have been barred from eating there were the few who had neither signed a preregistration application nor requested temporary meal tickets. Although the police were deployed near the campus in large numbers on three occasions, they did not at any time ‘ring’ the campus, and they were not called to the campus in connection with the demonstration on the State Capitol steps, as the third paragraph implied. Dr. King had not been arrested seven times, but only four; and although he claimed to have been assaulted some years earlier in connection with his arrest for loitering outside a courtroom, one of the officers who made the arrest denied that there was such an assault.

On the premise that the charges in the sixth paragraph could be read as referring to him, respondent was allowed to prove that he had not participated in the events described. Although Dr. King’s home had in fact been bombed twice when his wife and child were there, both of these occasions antedated respondent’s tenure as Commissioner, and the police were not only not implicated in the bombings, but had made every effort to apprehend those who were. Three of Dr. King’s four arrests took place before respondent became Commissioner. Although Dr. King had in fact been indicted (he was subsequently acquitted) on two counts of perjury, each of which carried a possible five-year sentence, respondent had nothing to do with procuring the indictment.

Respondent made no effort to prove that he suffered actual pecuniary loss as a result of the alleged libel.[2] One of his witnesses, a former employer, testified that if he had believed the statements, he doubted whether he ‘would want to be associated with anybody who would be a party to such things that are stated in that ad,’ and that he would not re-employ respondent if he believed ‘that he allowed the Police Department to do the things that the paper say he did.’ But neither this witness nor any of the others testified that he had actually believed the statements in their supposed reference to respondent. [***]

The trial judge submitted the case to the jury under instructions that the statements in the advertisement were ‘libelous per se’ and were not privileged, so that petitioners might be held liable if the jury found that they had published the advertisement and that the statements were made ‘of and concerning’ respondent.

The jury was instructed that, because the statements were libelous per se, ‘the law * * * implies legal injury from the bare fact of publication itself,’ ‘falsity and malice are presumed,’ ‘general damages need not be alleged or proved but are presumed,’ and ‘punitive damages may be awarded by the jury even though the amount of actual damages is neither found nor shown.’ An award of punitive damages—as distinguished from ‘general’ damages, which are compensatory in nature—apparently requires proof of actual malice under Alabama law, and the judge charged that ‘mere negligence or carelessness is not evidence of actual malice or malice in fact, and does not justify an award of exemplary or punitive damages.’ He refused to charge, however, that the jury must be ‘convinced’ of malice, in the sense of ‘actual intent’ to harm or ‘gross negligence and recklessness, to make such an award, and he also refused to require that a verdict for respondent differentiate between compensatory and punitive damages. The judge rejected petitioners’ contention that his rulings abridged the freedoms of speech and of the press that are guaranteed by the First and Fourteenth Amendments.

*717 In affirming the judgment, the Supreme Court of Alabama sustained the trial judge’s rulings and instructions in all respects. [c] It held that ‘(w)here the words published tend to injure a person libeled by them in his reputation, profession, trade or business, or charge him with an indictable offense, or tends to bring the individual into public contempt,’ they are ‘libelous per se’; that ‘the matter complained of is, under the above doctrine, libelous per se, if it was published of and concerning the plaintiff’; and that it was actionable without ‘proof of pecuniary injury * * *, such injury being implied.’ [c] It approved the trial court’s ruling that the jury could find the statements to have been made ‘of and concerning’ respondent, stating: ‘We think it common knowledge that the average person knows that municipal agents, such as police and firemen, and others, are under the control and direction of the city governing body, and more particularly under the direction and control of a single commissioner. In measuring the performance or deficiencies of such groups, praise or criticism is usually attached to the official in complete control of the body.’ [c]

In sustaining the trial court’s determination that the verdict was not excessive, the court said that malice could be inferred from the Times’ ‘irresponsibility’ in printing the advertisement while ‘the Times in its own files had articles already published which would have demonstrated the falsity of the allegations in the advertisement’; from the Times’ failure to retract for respondent while retracting for the Governor, whereas the falsity of some of the allegations was then known to the Times and ‘the matter contained in the advertisement was equally false as to both parties’; and from the testimony of the Times’ Secretary that, apart from the statement that the dining hall was padlocked, he thought the two paragraphs were ‘substantially correct.’ [c] The court reaffirmed a statement in an earlier opinion that ‘There is no legal measure of damages in cases of this character.’ [c] It rejected petitioners’ constitutional contentions with the brief statements that ‘The First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution does not protect libelous publications’ and ‘The Fourteenth Amendment is directed against State action and not private action.’ [c]

Because of the importance of the constitutional issues involved, we granted the separate petitions for certiorari of the individual petitioners and of the Times. [c] We reverse the judgment. We hold that the rule of law applied by the Alabama courts is constitutionally deficient for failure to provide the safeguards for freedom of speech and of the press that are required by the First and Fourteenth Amendments in a libel action brought by a public official against critics of his official conduct. [fn] *718 We further hold that under the proper safeguards the evidence presented in this case is constitutionally insufficient to support the judgment for respondent. [***]

Under Alabama law as applied in this case, a publication is ‘libelous per se’ if the words ‘tend to injure a person * * * in his reputation’ or to ‘bring (him) into public contempt’; the trial court stated that the standard was met if the words are such as to ‘injure him in his public office, or impute misconduct to him in his office, or want of official integrity, or want of fidelity to a public trust * * *.’ The jury must find that the words were published ‘of and concerning’ the plaintiff, but where the plaintiff is a public official his place in the governmental hierarchy is sufficient evidence to support a finding that his reputation has been affected by statements that reflect upon the agency of which he is in charge. Once ‘libel per se’ has been established, the defendant has no defense as to stated facts unless he can persuade the jury that they were true in all their particulars. [cc] His privilege of ‘fair comment’ for expressions of opinion depends on the truth of the facts upon which the comment is based. [c] Unless he can discharge the burden of proving truth, general damages are presumed, and may be awarded without proof of pecuniary injury. A showing of actual malice is apparently a prerequisite to recovery of punitive damages, and the defendant may in any event forestall a punitive award by a retraction meeting the statutory requirements. Good motives and belief in truth do not negate an inference of malice, but are relevant only in mitigation of punitive damages if the jury chooses to accord them weight. [c]

The question before us is whether this rule of liability, as applied to an action brought by a public official against critics of his official conduct, abridges the freedom of speech and of the press that is guaranteed by the First and Fourteenth Amendments. [Editor’s note: much of the discussion of the Fourteenth Amendment is omitted throughout the opinion.]

Respondent relies heavily, as did the Alabama courts, on statements of this Court to the effect that the Constitution does not protect libelous publications. [fn] Those statements do not foreclose our inquiry here. None of the cases sustained the use of libel laws to impose sanctions upon expression critical of the official conduct of public officials. [***] In the only previous case that did present the question of constitutional limitations upon the power to award damages for libel of a public official, the Court was equally divided and the question was not decided. [c] In deciding the question now, we are compelled by neither precedent nor policy to give any more weight to the epithet ‘libel’ than we have to other ‘mere labels’ of state law. [c] Like insurrection, [fn] contempt, [fn] advocacy of unlawful acts [fn], breach of the peace [fn], obscenity [fn ], solicitation of legal business [fn], and the various other formulae for the repression of expression that have been challenged in this Court, libel can claim no talismanic immunity from constitutional limitations. It must be measured by standards that satisfy the First Amendment.

The general proposition that freedom of expression upon public questions is secured by the First Amendment has long been settled by our decisions. The constitutional safeguard, we have said, ‘was fashioned to assure unfettered interchange of ideas for the bringing about of political and social changes desired by the people.’ [c] ‘The maintenance of the opportunity for free political discussion to the end that government may be responsive to the will of the people and that changes may be obtained by lawful means, an opportunity essential to the security of the Republic, is a fundamental principle of our constitutional system.’ [c] ‘(I)t is a prized American privilege to speak one’s mind, although not always with perfect good taste, on all public institutions,’ [c] and this opportunity is to be afforded for ‘vigorous advocacy’ no less than ‘abstract discussion.’ [c]

The First Amendment, said Judge Learned Hand, ‘presupposes that right conclusions are more likely to be gathered out of a multitude of tongues, than through any kind of authoritative selection. To many this is, and always will be, folly; but we have staked upon it our all.’ United States v. Associated Press, 52 F. Supp. 362, 372 (D.C.S.D.N.Y.1943). Mr. Justice Brandeis, in his concurring opinion in Whitney v. California, 274 U.S. 357, 375—376, gave the principle its classic formulation:

‘Those who won our independence believed * * * that public discussion is a political duty; and that this should be a fundamental principle of the American government. They recognized the risks to which all human institutions are subject. But they knew that order cannot be secured merely through fear of punishment for its infraction; that it is hazardous to discourage thought, *721 hope and imagination; that fear breeds repression; that repression breeds hate; that hate menaces stable government; that the path of safety lies in the opportunity to discuss freely supposed grievances and proposed remedies; and that the fitting remedy for evil counsels is good ones. Believing in the power of reason as applied through public discussion, they eschewed silence coerced by law—the argument of force in its worst form. Recognizing the occasional tyrannies of governing majorities, they amended the Constitution so that free speech and assembly should be guaranteed.’

Thus we consider this case against the background of a profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials. [cc] The present advertisement, as an expression of grievance and protest on one of the major public issues of our time, would seem clearly to qualify for the constitutional protection. The question is whether it forfeits that protection by the falsity of some of its factual statements and by its alleged defamation of respondent.

Authoritative interpretations of the First Amendment guarantees have consistently refused to recognize an exception for any test of truth—whether administered by judges, juries, or administrative officials—and especially one that puts the burden of proving truth on the speaker. [c] The constitutional protection does not turn upon ‘the truth, popularity, or social utility of the ideas and beliefs which are offered.’ [c] As Madison said, ‘Some degree of abuse is inseparable from the proper use of everything; and in no instance is this more true than in that of the press.’ [c] [***]

That erroneous statement is inevitable in free debate, and that it must be protected if the freedoms of expression are to have the ‘breathing space’ that they ‘need * * * to survive,’ [c] was also recognized by the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit [c]. Judge Edgerton spoke for a unanimous court which affirmed the dismissal of a Congressman’s libel suit based upon a newspaper article charging him with anti-Semitism in opposing a judicial appointment. He said:

‘Cases which impose liability for erroneous reports of the political conduct of officials reflect the obsolete doctrine that the governed must not criticize their governors. * * * The interest of the public here outweighs the interest of appellant *722 or any other individual. The protection of the public requires not merely discussion, but information. Political conduct and views which some respectable people approve, and others condemn, are constantly imputed to Congressmen. Errors of fact, particularly in regard to a man’s mental states and processes, are inevitable. * * * Whatever is added to the field of libel is taken from the field of free debate.’[3]

Injury to official reputation error affords no more warrant for repressing speech that would otherwise be free than does factual error. Where judicial officers are involved, this Court has held that concern for the dignity and *273 reputation of the courts does not justify the punishment as criminal contempt of criticism of the judge or his decision. [c] This is true even though the utterance contains ‘half-truths’ and ‘misinformation.’ [c] Such repression can be justified, if at all, only by a clear and present danger of the obstruction of justice. [cc] If judges are to be treated as ‘men of fortitude, able to thrive in a hardy climate,’ [c] surely the same must be true of other government officials, such as elected city commissioners.[4] Criticism of their official conduct does not lose its constitutional protection merely because it is effective criticism and hence diminishes their official reputations.

If neither factual error nor defamatory content suffices to remove the constitutional shield from criticism of official conduct, the combination of the two elements is no less inadequate. This is the lesson to be drawn from the great controversy over the Sedition Act of 1798, 1 Stat. 596, which first crystallized a national awareness of the central meaning of the First Amendment.

[The Court discusses the Sedition Act of 1798, which made it a crime, punishable by a $5,000 fine and five years in prison, ‘if any person shall write, print, utter or publish * * * any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States, or either house of the Congress * * *, or the President * * *, with intent to defame * * * or to bring them, or either of them, into contempt or disrepute; or to excite against them, or either or any of them, the hatred of the good people of the United States.’ The Act expired in 1801, but the Court concludes here that it was unconstitutional.]

What a State may not constitutionally bring about by means of a criminal statute is likewise beyond the reach of its civil law of libel. [fn] The fear of damage awards under a rule such as that invoked by the Alabama courts here may be markedly more inhibiting than the fear of prosecution under a criminal statute. [c] Alabama, for example, has a criminal libel law which subjects to prosecution ‘any person who speaks, writes, or prints of and concerning another any accusation falsely and maliciously importing the commission by such person of a felony, or any other indictable offense involving moral turpitude,’ and which allows as punishment upon conviction a fine not exceeding $500 and a prison sentence of six months. Alabama Code, Tit. 14, s 350. Presumably a person charged with violation of this statute enjoys ordinary criminal-law safeguards such as the requirements of an indictment and of proof beyond a reasonable doubt. These safeguards are not available to the defendant in a civil action.

The judgment awarded in this case—without the need for any proof of actual pecuniary loss—was one thousand times greater than the maximum fine provided by the Alabama criminal statute, and one hundred times greater than that provided by the Sedition Act. And since there is no double-jeopardy limitation applicable to civil *725 lawsuits, this is not the only judgment that may be awarded against petitioners for the same publication.[5] Whether or not a newspaper can survive a succession of such judgments, the pall of fear and timidity imposed upon those who would give voice to public criticism is an atmosphere in which the First Amendment freedoms cannot survive. Plainly the Alabama law of civil libel is ‘a form of regulation that creates hazards to protected freedoms markedly greater than those that attend reliance upon the criminal law.’ [c]

The state rule of law is not saved by its allowance of the defense of truth. A defense for erroneous statements honestly made is no less essential here than was the requirement of proof of guilty knowledge which, in Smith v. California, 361 U.S. 147, we held indispensable to a valid conviction of a bookseller for possessing obscene writings for sale. We said:

‘For if the bookseller is criminally liable without knowledge of the contents, * * * he will tend to restrict the books he sells to those he has inspected; and thus the State will have imposed a restriction upon the distribution of constitutionally protected as well as obscene literature. * * * And the bookseller’s burden would become the public’s burden, for by restricting him the public’s access to reading matter would be restricted. * * * (H)is timidity in the face of his absolute criminal liability, thus would tend to restrict the public’s access to forms of the printed word which the State could not constitutionally * suppress directly. The bookseller’s self-censorship, compelled by the State, would be a censorship affecting the whole public, hardly less virulent for being privately administered. Through it, the distribution of all books, both obscene and not obscene, would be impeded.’ [c]

A rule compelling the critic of official conduct to guarantee the truth of all his factual assertions—and to do so on pain of libel judgments virtually unlimited in amount—leads to a comparable ‘self-censorship.’ Allowance of the defense of truth, with the burden of proving it on the defendant, does not mean that only false speech will be deterred.[6] Even courts accepting this defense as an adequate safeguard have recognized the difficulties of adducing legal proofs that the alleged libel was true in all its factual particulars. [cc] Under such a rule, would-be critics of official conduct may be deterred from voicing their criticism, even though it is believed to be true and even though it is in fact true, because of doubt whether it can be proved in court or fear of the expense of having to do so. They tend to make only statements which ‘steer far wider of the unlawful zone.’ [c] The rule thus dampens the vigor and limits the variety of public debate. It is *726 inconsistent with the First and Fourteenth Amendments.

The constitutional guarantees require, we think, a federal rule that prohibits a public official from recovering damages for a defamatory falsehood relating to his official conduct unless he proves that the statement was made with ‘actual malice’—that is, with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not. An oft-cited statement of a like rule, which has been adopted by a number of state courts, [fn] is found in the Kansas case of Coleman v. MacLennan, 78 Kan. 711 (1908). The State Attorney General, a candidate for re-election and a member of the commission charged with the management and control of the state school fund, sued a newspaper publisher for alleged libel in an article purporting to state facts relating to his official conduct in connection with a school-fund transaction. The defendant pleaded privilege and the trial judge, over the plaintiff’s objection, instructed the jury that

‘where an article is published and circulated among voters for the sole purpose of giving what the defendant * believes to be truthful information concerning a candidate for public office and for the purpose of enabling such voters to cast their ballot more intelligently, and the whole thing is done in good faith and without malice, the article is privileged, although the principal matters contained in the article may be untrue in fact and derogatory to the character of the plaintiff; and in such a case the burden is on the plaintiff to show actual malice in the publication of the article.’

In answer to a special question, the jury found that the plaintiff had not proved actual malice, and a general verdict was returned for the defendant. On appeal the Supreme Court of Kansas, in an opinion by Justice Burch, reasoned as follows (78 Kan., at 724, 98 P., at 286):

‘(I)t is of the utmost consequence that the people should discuss the character and qualifications of candidates for their suffrages. The importance to the state and to society of such discussions is so vast, and the advantages derived are so great that they more than counterbalance the inconvenience of private persons whose conduct may be involved, and occasional injury to the reputations of individuals must yield to the public welfare, although at times such injury may be great. The *727 public benefit from publicity is so great and the chance of injury to private character so small that such discussion must be privileged.’

The court thus sustained the trial court’s instruction as a correct statement of the law, saying:

‘In such a case the occasion gives rise to a privilege qualified to this extent. Anyone claiming to be defamed by the communication must show actual malice, or go remediless. This privilege extends to a great variety of subjects and includes matters of * public concern, public men, and candidates for office.’ [c]

Such a privilege for criticism of official conduct[7] is appropriately analogous to the protection accorded a public official when he is sued for libel by a private citizen. In Barr v. Matteo, 360 U.S. 564, 575, this Court held the utterance of a federal official to be absolutely privileged if made ‘within the outer perimeter’ of his duties. The States accord the same immunity to statements of their highest officers, although some differentiate their lesser officials and qualify the privilege they enjoy. [fn] But all hold that all officials are protected unless actual malice can be proved. The reason for the official privilege is said to be that the threat of damage suits would otherwise ‘inhibit the fearless, vigorous, and effective administration of policies of government’ and ‘dampen the ardor of all but the most resolute, or the most irresponsible, in the unflinching discharge of their duties.’ [c]

Analogous considerations support the privilege for the citizen-critic of government. It is as much his duty to criticize as it is the official’s duty to administer. [c] As Madison said, see supra, p. 723, ‘the censorial power is in the people over the Government, and not in the Government over the people.’ It would give public servants an unjustified preference over the public they serve, if critics of official conduct did not have a fair equivalent of the immunity granted to the officials themselves.

We conclude that such a privilege is required by the First and Fourteenth Amendments.

We hold today that the Constitution delimits a State’s power to award damages for libel in actions brought by public officials against critics of their official conduct. Since this is such an action,[8] the rule requiring proof of actual malice is applicable. While *728 Alabama law apparently requires proof of actual malice for an award of punitive damages,[9] where general damages are concerned malice is ‘presumed.’ Such a presumption is inconsistent with the federal rule. ‘The power to create presumptions is not a means of escape from constitutional restrictions,’ [c]; ‘(t)he showing of malice required for the forfeiture of the privilege is not presumed but is a matter for proof by the plaintiff * * *.’ [c] Since the trial judge did not instruct the jury to differentiate between general and punitive damages, it may be that the verdict was wholly an award of one or the other. But it is impossible to know, in view of the general verdict returned. Because of this uncertainty, the judgment must be reversed and the case remanded. [cc]

Since respondent may seek a new trial, we deem that considerations of effective judicial administration require us to review the evidence in the present record to determine whether it could constitutionally support a judgment for respondent. This Court’s duty is not limited to the elaboration of constitutional principles; we must also in proper cases review the evidence to make certain that those principles have been constitutionally applied. This is such a case, particularly since the question is one of alleged trespass across ‘the line between speech unconditionally guaranteed and speech which may legitimately be regulated.’ [c] [***]

Applying these standards, we consider that the proof presented to show actual malice lacks the convincing clarity which the constitutional standard demands, and hence that it would not constitutionally sustain the judgment for respondent under the proper rule of law. The case of the individual petitioners requires little discussion. Even assuming that they could constitutionally be found to have authorized the use of their names on the advertisement, there was no evidence whatever that they were aware of any erroneous statements or were in any way reckless in that regard. The judgment against them is thus without constitutional support.

As to the Times, we similarly conclude that the facts do not support a finding of actual malice. The statement by the Times’ Secretary that, apart from the padlocking allegation, he thought the advertisement was ‘substantially correct,’ affords no constitutional warrant for the Alabama Supreme Court’s conclusion that it was a ‘cavalier ignoring of the falsity of the advertisement (from which), the jury could not have but been impressed with the bad faith of The Times, and its maliciousness inferable therefrom.’ The statement does not indicate malice at the time of the publication; even if the advertisement was not ‘substantially correct’—although respondent’s own proofs tend to show that it was—that opinion was at least a reasonable one, and there was no evidence to impeach the witness’ good faith in holding it. The Times’ failure to retract upon respondent’s demand, although it later retracted upon the demand of Governor Patterson, is likewise not adequate evidence of malice for constitutional purposes. Whether or not a failure to retract may ever constitute such evidence, there are two reasons why it does not here.

First, the letter written by the Times reflected a reasonable doubt on its part as to whether the advertisement could reasonably be taken to refer to respondent at all. Second, it was not a final refusal, since it asked for an explanation on this point—a request that respondent chose to ignore. Nor does the retraction upon the demand of the Governor supply the necessary proof. It may be doubted that a failure to retract which is not itself evidence of malice can retroactively become such by virtue of a retraction subsequently made to another party. But in any event that did not happen here, since the *730 explanation given by the Times’ Secretary for the distinction drawn between respondent and the Governor was a reasonable one, the good faith of which was not impeached.

Finally, there is evidence that the Times published the advertisement without checking its accuracy against the news stories in the Times’ own files. The mere presence of the stories in the files does not, of course, establish that the Times ‘knew’ the advertisement was false, since the state of mind required for actual malice would have to be brought home to the persons in the Times’ organization having responsibility for the publication of the advertisement. With respect to the failure of those persons to make the check, the record shows that they relied upon their knowledge of the good reputation of many of those whose names were listed as sponsors of the advertisement, and upon the letter from A. Philip Randolph, known to them as a responsible individual, certifying that the use of the names was authorized. There was testimony that the persons handling the advertisement saw nothing in it that would render it unacceptable under the Times’ policy of rejecting advertisements containing ‘attacks of a personal character’;[10] their failure to reject it on this ground was not unreasonable. We think the evidence against the Times supports at most a finding of negligence in failing to discover the misstatements, and is constitutionally insufficient to show the recklessness that is required for a finding of actual malice. [cc]

We also think the evidence was constitutionally defective in another respect: it was incapable of supporting the jury’s finding that the allegedly libelous statements were made ‘of and concerning’ respondent. Respondent relies on the words of the advertisement and the testimony of six witnesses to establish a connection between it and himself. Thus, in his brief to this Court, he states:

‘The reference to respondent as police commissioner is clear from the ad. In addition, the jury heard the testimony of a newspaper editor * * *; a real estate and insurance man * * *; the sales manager of a men’s clothing store * * *; a food equipment man * * *; a service station operator * * *; and the operator of a truck line for whom respondent had formerly worked * * *. Each of these witnesses stated that he associated the statements with respondent * * *.’ (Citations to record omitted.)

There was no reference to respondent in the advertisement, either by name or official position. A number of the allegedly libelous statements—the charges that the dining hall was padlocked and that Dr. King’s home was bombed, his person assaulted, and a perjury prosecution instituted against him—did not even concern the police; despite the ingenuity of the arguments which would attach this significance to the word ‘They,’ it is plain that these statements could not reasonably be read as accusing respondent of personal involvement in the acts in question. The statements upon which respondent *731 principally relies as referring to him are the two allegations that did concern the police or police functions: that ‘truckloads of police * * * ringed the Alabama State College Campus’ after the demonstration on the State Capitol steps, and that Dr. King had been arrested * * * seven times.’ These statements were false only in that the police had been ‘deployed near’ the campus but had not actually ‘ringed’ it and had not gone there in connection with the State Capitol demonstration, and in that Dr. King had been arrested only four times. The ruling that these discrepancies between what was true and what was asserted were sufficient to injure respondent’s reputation may itself raise constitutional problems, but we need not consider them here.

Although the statements may be taken as referring to the police, they did not on their face make even an oblique reference to respondent as an individual. Support for the asserted reference must, therefore, be sought in the testimony of respondent’s witnesses. But none of them suggested any basis for the belief that respondent himself was attacked in the advertisement beyond the bare fact that he was in overall charge of the Police Department and thus bore official responsibility for police conduct; to the extent that some of the witnesses thought respondent to have been charged with ordering or approving the conduct or otherwise being personally involved in it, they based this notion not on any statements in the advertisement, and not on any evidence that he had in fact been so involved, but solely on the unsupported assumption that, because of his official position, he must have been.[11] This reliance on the bare fact of respondent’s *732 official position [fn] was made explicit by the Supreme Court of Alabama. That court, in holding that the trial court ‘did not err in overruling the demurrer (of the Times) in the aspect that the libelous matter was not of and concerning the (plaintiff,)’ based its ruling on the proposition that:

‘We think it common knowledge that the average person knows that municipal agents, such as police and firemen, and others, are under the control and direction of the city governing body, and more particularly under the direction and control of a single commissioner. In measuring the performance or deficiencies of such groups, praise or criticism is usually attached to the official in complete control of the body.’ 273 Ala., at 674—675.

This proposition has disquieting implications for criticism of governmental conduct. For good reason, ‘no court of last resort in this country has ever held, or even suggested, that prosecutions for libel on government have any place in the American system of jurisprudence.’ City of Chicago v. Tribune Co., 307 Ill. 595, 601 (1923).

The present proposition would sidestep this obstacle by transmuting criticism of government, however impersonal it may seem on its face, into personal criticism, and hence potential libel, of the officials of whom the government is composed. There is no legal alchemy by which a State may thus create the cause of action that would otherwise be denied for a publication which, as respondent himself said of the advertisement, ‘reflects not only on me but on the other Commissioners and the community.’ Raising as it does the possibility that a good-faith critic of government will be penalized for his criticism, the proposition relied on by the Alabama courts strikes at the very center of the constitutionally protected area of free expression.[12]

We hold that such a proposition may not constitutionally be utilized to establish that an otherwise impersonal attack on governmental operations was a libel of an official responsible for those operations. Since it was relied on exclusively here, and there was no other evidence to connect the statements with respondent, the evidence was constitutionally insufficient to support a finding that the statements referred to respondent.

*733 The judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabama is reversed and the case is remanded to that court for further proceedings not inconsistent with this opinion.

Reversed and remanded.

Concurrence of Justice Black, joined by Justice Douglas

I concur in reversing this half-million-dollar judgment against the New York Times Company and the four individual defendants. In reversing the Court holds that ‘the Constitution delimits a State’s power to award damages for libel in actions brought by public officials against critics of their official conduct.’ Ante, p. 727. I base my vote to reverse on the belief that the First and Fourteenth Amendments do not merely ‘delimit’ a State’s power to award damages to ‘public officials against critics of their official conduct’ but completely prohibit a State from exercising such a power. The Court goes on to hold that a State can subject such critics to damages if ‘actual malice’ can be proved against them.

‘Malice,’ even as defined by the Court, is an elusive, abstract concept, hard to prove and hard to disprove. The requirement that malice be proved provides at best an evanescent protection for the right critically to discuss public affairs and certainly does not measure up to the sturdy safeguard embodied in the First Amendment. Unlike the Court, therefore, I vote to reverse exclusively on the ground that the Times and the individual defendants had an absolute, unconditional constitutional right to publish in the Times advertisement their criticisms of the Montgomery agencies and officials. I do not base my vote to reverse on any failure to prove that these individual defendants signed the advertisement or that their criticism of the Police Department was aimed at the plaintiff Sullivan, who was then the Montgomery City Commissioner having supervision of the City’s police; for present purposes I assume these things were proved. Nor is my reason for reversal the size of the half-million-dollar judgment, large as it is. If Alabama has constitutional power to use its civil libel law to impose damages on the press for criticizing the way public officials perform or fail to perform their duties, I know of no provision in the Federal Constitution which either expressly or impliedly bars the State from fixing the amount of damages.

The half-million-dollar verdict does give dramatic proof, however, that state libel laws threaten the very existence of an American press virile enough to publish unpopular views on public affairs and bold enough to criticize the conduct of public officials. The factual background of this case emphasizes the imminence and enormity of that threat. One of the acute and highly emotional issues in this country arises out of efforts of many people, even including some public officials, to continue state-commanded segregation of races in the public schools and other public places, despite our several holdings that such a state practice is forbidden by the Fourteenth Amendment.

Montgomery is one of the localities in which widespread hostility to desegregation has been manifested. This hostility has sometimes extended itself to persons who favor desegregation, particularly to so-called ‘outside agitators,’ a term which can be made to fit papers like the Times, which is published in New York. The scarcity of testimony to show that Commissioner Sullivan suffered any actual damages at all suggests that these feelings of hostility had at least as much to do with rendition of this half-million-dollar verdict as did an appraisal of damages. Viewed realistically, this record lends support to an inference that instead of being damaged Commissioner Sullivan’s political, social, and financial prestige has likely been enhanced by the Times’ publication. Moreover, a second half-million-dollar libel verdict against the Times based on the same advertisement has already been *734 awarded to another Commissioner.

There a jury again gave the full amount claimed. There is no reason to believe that there are not more such huge verdicts lurking just around the corner for the Times or any other newspaper or broadcaster which might dare to criticize public officials. In fact, briefs before us show that in Alabama there are now pending eleven libel suits by local and state officials against the Times seeking $5,600,000, and five such suits against the Columbia Broadcasting System seeking $1,700,000. Moreover, this technique for harassing and punishing a free press—now that it has been shown to be possible—is by no means limited to cases with racial overtones; it can be used in other fields where public feelings may make local as well as out-of-state newspapers easy prey for libel verdict seekers.

In my opinion the Federal Constitution has dealt with this deadly danger to the press in the only way possible without leaving the free press open to destruction—by granting the press an absolute immunity for criticism of the way public officials do their public duty. [c] Stopgap measures like those the Court adopts are in my judgment not enough. This record certainly does not indicate that any different verdict would have been rendered here whatever the Court had charged the jury about ‘malice,’ ‘truth,’ ‘good motives,’ ‘justifiable ends,’ or any other legal formulas which in theory would protect the press. Nor does the record indicate that any of these legalistic words would have caused the courts below to set aside or to reduce the half-million-dollar verdict in any amount. [***]

We would, I think, more faithfully interpret the First Amendment by holding that at the very least it leaves the people and the press free to criticize officials and discuss public affairs with impunity. This Nation of our elects many of its important officials; so do the States, the municipalities, the counties, and even many precincts. These officials are responsible to the people for the way they perform their duties. While our Court has held that some kinds of speech and writings, such as ‘obscenity,’ *735 Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476, and ‘fighting words,’ Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U.S. 568, are not expression within the protection of the First Amendment [c], freedom to discuss public affairs and public officials is unquestionably, as the Court today holds, the kind of speech the First Amendment was primarily designed to keep within the area of free discussion. To punish the exercise of this right to discuss public affairs or to penalize it through libel judgments is to abridge or shut off discussion of the very kind most needed.

This Nation, I suspect, can live in peace without libel suits based on public discussions of public affairs and public officials. But I doubt that a country can live in freedom where its people can be made to suffer physically or financially for criticizing their government, its actions, or its officials. ‘For a representative democracy ceases to exist the moment that the public functionaries are by any means absolved from their responsibility to their constituents; and this happens whenever the constituent can be restrained in any manner from speaking, writing, or publishing his opinions upon any public measure, or upon the conduct of those who may advise or execute it.’[13] An unconditional right to say what one pleases about public affairs is what I consider to be the minimum guarantee of the First Amendment. [fn] I regret that the Court has stopped short of this holding indispensable to preserve our free press from destruction.

Concurrence by Justice Goldberg, joined by Justice Douglas

The Court today announces a constitutional standard which prohibits ‘a public official from recovering damages for a defamatory falsehood relating to his official conduct unless he proves that the statement was made with ‘ACTUAL MALICE’—THAT IS, WITH KNOWLEDGE that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.’ Ante, at p. 726. The Court thus rules that the Constitution gives citizens and newspapers a ‘conditional privilege’ immunizing nonmalicious misstatements of fact regarding the official conduct of a government officer. The impressive array of history[14] and precedent marshaled by the Court, however, confirms my belief that the Constitution affords greater protection than that provided by the Court’s standard to citizen and press in exercising the right of public criticism.

In my view, the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution afford to the citizen and to the press an absolute, unconditional privilege to criticize official conduct despite the harm which may flow from excesses and abuses. The prized American right ‘to speak one’s *736 mind,’ [c] about public officials and affairs needs ‘breathing space to survive,’ [c]. The right should not depend upon a probing by the jury of the motivation[15] of the citizen or press. The theory of our Constitution is that every citizen may speak his mind and every newspaper express its view on matters of public concern and may not be barred from speaking or publishing because those in control of government think that what is said or written is unwise, unfair, false, or malicious. In a democratic society, one who assumes to act for the citizens in an executive, legislative, or judicial capacity must expect that his official acts will be commented upon and criticized. Such criticism cannot, in my opinion, be muzzled or deterred by the courts at the instance of public officials under the label of libel.

It has been recognized that ‘prosecutions for libel on government have (no) place in the American system of jurisprudence.’ City of Chicago v. Tribune Co., 307 Ill. 595, 601. I fully agree. Government, however, is not an abstraction; it is made up of individuals—of governors responsible to the governed. In a democratic society where men are free by ballots to remove those in power, any statement critical of governmental action is necessarily ‘of and concerning’ the governors and any statement critical of the governors’ official conduct is necessarily ‘of and concerning’ the government. If the rule that libel on government has no place in our Constitution is to have real meaning, then libel on the official conduct of the governors likewise can have no place in our Constitution.

We must recognize that we are writing upon a clean slate.[16] As the Court notes, although there have been ‘statements of this Court to the effect that the Constitution does not protect libelous publications * * * (n)one of the cases sustained the use of libel laws to impose sanctions upon expression critical of the official conduct of public officials.’ Ante, at p. 719. *737 [***]

[The real issue here] is whether that freedom of speech which all agree is constitutionally protected can be effectively safeguarded by a rule allowing the imposition of liability upon a jury’s evaluation of the speaker’s state of mind. If individual citizens may be held liable in damages for strong words, which a jury finds false and maliciously motivated, there can be little doubt that public debate and advocacy will be constrained. And if newspapers, publishing advertisements dealing with public issues, thereby risk liability, there can also be little doubt that the ability of minority groups to secure publication of their views on public affairs and to seek support for their causes will be greatly diminished. [c] The opinion of the Court conclusively demonstrates the chilling effect of the Alabama libel laws on First Amendment freedoms in the area of race relations. [***]To impose liability for critical, albeit erroneous or even malicious, comments on official conduct would effectively resurrect ‘the obsolete doctrine that the governed must not criticize their governors.’ [c]

Our national experience teaches that repressions breed hate and ‘that hate menaces stable government.’ [c]. We should be ever mindful of the wise counsel of Chief Justice Hughes:

‘(I)mperative is the need to preserve inviolate the constitutional rights of free speech, free press and free assembly in order to maintain the opportunity for free political discussion, to the end that government may be responsive to the will of the people and that changes, if desired, may be obtained by peaceful means. Therein lies the security of the Republic, the very foundation of constitutional government.’ [c]

This is not to say that the Constitution protects defamatory statements directed against the private conduct of a public official or private citizen. Freedom of press and of speech ensures that government will respond to the will of the people and that changes may be obtained by peaceful means. [c] [***] The imposition of liability for private defamation does not abridge the freedom of public speech or any other freedom protected by the First Amendment.[17] This, of course, cannot be said ‘where *738 public officials are concerned or where public matters are involved. * * * (O)ne main function of the First Amendment is to ensure ample opportunity for the people to determine and resolve public issues. Where public matters are involved, the doubts should be resolved in favor of freedom of expression rather than against it.’ Douglas, The Right of the People (1958), p. 41.

In many jurisdictions, legislators, judges and executive officers are clothed with absolute immunity against liability for defamatory words uttered in the discharge of their public duties. [c]

Judge Learned Hand ably summarized the policies underlying the rule:

‘It does indeed go without saying that an official, who is in fact guilty of using his powers to vent his spleen upon others, or for any other personal motive not connected with the public good, should not escape liability for the injuries he may so cause; and, if it were possible in practice to confine such complaints to the guilty, it would be monstrous to deny recovery. The justification for doing so is that it is impossible to know whether the claim is well founded until the case has been tried, and that to submit all officials, the innocent as well as the guilty, to the burden of a trial and to the inevitable danger of its outcome, would dampen the ardor of all but the most resolute, or the most irresponsible, in the unflinching discharge of their duties. Again and again the public interest calls for action which may turn out to be founded on a mistake, in the face of which an official may later find himself hard put to it to satisfy a jury of his good faith. There must indeed be means of punishing public officers who have been truant to their duties; but that is quite another matter from exposing such as have been honestly mistaken to suit by anyone who has suffered from their errors. As is so often the case, the answer must be found in a balance between the evils inevitable in either alternative. In this instance it has been thought in the end better to leave unredressed the wrongs done by dishonest officers than to subject those who try to do their duty to the constant dread of retaliation. * * * [***] [c]

If the government official should be immune from libel actions so that his ardor to serve the public will not be dampened and ‘fearless, vigorous, and effective administration of policies of government’ not be inhibited, [c], then the citizen and the press should likewise be immune from libel actions for their criticism of official conduct. Their ardor as citizens will thus not be dampened and they will *739 be free ‘to applaud or to criticize the way public employees do their jobs, from the least to the most important.’ If liability can attach to political criticism because it damages the reputation of a public official as a public official, then no critical citizen can safely utter anything but faint praise about the government or its officials. The vigorous criticism by press and citizen of the conduct of the government of the day by the officials of the day will soon yield to silence if officials in control of government agencies, instead of answering criticisms, can resort to friendly juries to forestall criticism of their official conduct.

The conclusion that the Constitution affords the citizen and the press an absolute privilege for criticism of official conduct does not leave the public official without defenses against unsubstantiated opinions or deliberate misstatements. ‘Under our system of government, counterargument and education are the weapons available to expose these matters, not abridgment * * * of free speech * * *.’ [c] The public official certainly has equal if not greater access than most private citizens to media of communication. In any event, despite the possibility that some excesses and abuses may go unremedied, we must recognize that ‘the people of this nation have ordained in the light of history, that, in spite of the probability of excesses and abuses, (certain) liberties are, in the long view, essential to enlightened opinion and right conduct on the part of the citizens of a democracy.’ [c] As Mr. Justice Brandeis correctly observed, ‘sunlight is the most powerful of all disinfectants.’

For these reasons, I strongly believe that the Constitution accords citizens and press an unconditional freedom to criticize official conduct. It necessarily follows that in a case such as this, where all agree that the allegedly defamatory statements related to official conduct, the judgments for libel cannot constitutionally be sustained.

Note 1. “Heed Their Rising Voices” is viewable via Wikipedia.

Credit: Public Domain. Reproduction of a copy kept in the archives of the U.S. District Court for the Northern (Montgomery) Division of the Middle District of Alabama.

Note 2. Political or Ideological Arguments. Shifting from state courts and even circuit courts to the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence often entails diving into longer opinions and complex analyses that may involve theory and history. This is especially true with respect to the First Amendment in the Sullivan era, in which new case law and standards were being developed and would continue to unfold for about two decades. The area is highly political (which remains true today). Defamation’s constitutional jurisprudence delivers sketches of judicial philosophy to a greater extent than introductory torts materials typically do, thus permitting law students to begin to identify particular kinds of arguments and align them with judicial and political philosophies of law. Can you identify two to three arguments that are expressly political or ideological? What sorts of evidence and rationales do you observe in the justices’ legal reasoning?

Note 3. How strong was “truth” as a defense in Alabama? What do you make of that?

Note 4. How robust does Alabama’s “of and concerning” requirement appear to be?

Note 5. How relevant do you think it was that the dispute occurred in the context of the Civil Rights Movement and Alabama’s role in resisting those efforts (with persistently segregationist policies, for instance)? Do your normative views of the clash between defamation and the First Amendment change depending on the context. If so, how so?

Note 6. Burdens of Proof. Sullivan kicked off an era of constitutionalization of defamation law that resulted in several lasting changes. One of these is that the court heightened the level of proof to be applied when determining various issues from a preponderance of the evidence to a “clear and convincing” standard. This higher standard applies to the issues of falsity, actual malice (knowledge of falsity or reckless disregard for the truth) and the “of and concerning” requirement, in cases involving public officials. New York Times, 376 U.S. at 284-85, 288-289. Subsequent cases extended this change to plaintiffs who are public figures (or limited-purpose public figures), and the higher standard often also applies when the person is a private figure involved in a matter of public or general concern.

Note 7. Justice Black’s concurrence faults the majority for not going far enough. What does he believe the First Amendment permits? What is he concerned about with respect to actual malice?

Note 8. What is Justice Black concerned about with respect to damages? Why does it seem especially pressing to him at the time of the ruling and on the facts of this case?

Note 9. Like Justice Black, Justice Goldberg calls for recognition of an “absolute, unconditional privilege to criticize official conduct despite the harm which may flow from excesses and abuses.” However, Goldberg’s emphasis and arguments are somewhat different. What arguments and concerns do you identify in his concurrence?

Note 10. The Difficulty of Deciding Defamation Disputes as a Matter of Law. Due to Sullivan and its progeny, the precise culpability standard in defamation varies a great deal, depending on both the speaker and the person about whom the statement is made. Like IIED (which uses “intentional conduct or recklessness” for its culpability standard), defamation in the modern era can come with Sullivan’s special “actual malice” standard. Public officials (such as the government actor in Sullivan) receive less protection from accidentally false speech. You can think of this almost like a kind of immunity for the rest of us, that is, as a privilege for speakers who wish to criticize the government or its officials. A commitment to robust freedom of expression about the government justifies imposing heightened protection for speech about public officials, and the way the tort of defamation accomplishes this is by heightening the culpability standard the plaintiff must satisfy. In the wake of Sullivan, however, the same rationale has been extended from public officials to “public figures,” such as celebrities. Like government officials, public figures similarly face higher hurdles to recover in defamation cases. Similarly, private citizens involved in matters of public concern are treated as public figures with respect to speech related to the matter of public concern.

The kinds of precautions a speaker must take to avoid charges of negligence can vary greatly depending on the circumstances. Defamation tends to be difficult to dismiss during early stages of a dispute because of the factual evidence needed to determine what the speaker knew or should have known and to evaluate the conditions under which they spoke. Further, whether something is capable of carrying defamatory meaning can be a difficult factual inquiry; whether it actually communicated defamatory meaning to the communication’s recipients is yet another; and whether the recipients of the communications understood them to be about this plaintiff is still a third. You have likely seen by now that many product liability and general negligence cases are quite fact-intensive; almost all defamation cases are equally or even more so.

Think back to Module 3’s discussions of duty as a judicial gatekeeping doctrine versus proximate cause as a liability limiting principle determined by the jury as a matter of fact. What arguments might you make in favor of facilitating dismissal of defamation cases on early motions as a matter of law (in a manner similar deciding to duty) versus letting defamation disputes proceed to a full factual record (in a manner similar to deciding proximate cause)? What is the right balance between the various interests protected, descriptively and normatively? What is the appropriate legal mechanism for achieving that balance, do you think?

Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc., Supreme Court of the United States (1974)

(418 U.S. 323)

Mr. Justice POWELL delivered the opinion of the Court.

This Court has struggled for nearly a decade to define the proper accommodation between the law of defamation and the freedoms of speech and press protected by the First Amendment. With this decision we return to that effort. We granted certiorari to reconsider the extent of a publisher’s constitutional privilege against liability for defamation of a private citizen. 410 U.S. 925 (1973).

*323 [Summary of facts: A Chicago policeman named Nuccio was convicted of murder. The victim’s family retained petitioner, Elmer Gertz, a reputable attorney, to represent them in civil litigation against Nuccio. Respondent Robert Welch’s magazine, American Opinion, which was published by the ultra-conservative John Birch society, featured an article that about Nuccio’s murder trial. The magazine alleged that the trial was part of a Communist conspiracy to discredit the local police, it falsely stated that petitioner Gertz had arranged Nuccio’s ‘frameup,’ it implied that Gertz had a criminal record, and falsely identified his political beliefs.] [***]

*326 In his capacity as counsel for the Nelson [victim’s] family in the civil litigation, Gertz attended the coroner’s inquest into the boy’s death and initiated actions for damages, but he neither discussed Officer Nuccio with the press nor played any part in the criminal proceeding. Notwithstanding Gertz’s remote connection with the prosecution of Nuccio, Welch’s magazine portrayed him as an architect of the ‘frameup.’ According to the article, the police file on petitioner took ‘a big, Irish cop to lift,’ The article stated that Gertz had been an official of the ‘Marxist League for Industrial Democracy, originally known as the Intercollegiate Socialist Society, which has advocated the violent seizure of our government.’ It labeled Gertz a ‘Leninist’ and a ‘Communist-fronter.’ It also stated that Gertz had been an officer of the National Lawyers Guild, described as a Communist organization that ‘probably did more than any other outfit to plan the Communist attack on the Chicago police during the 1968 Democratic Convention.’

These statements contained serious inaccuracies. The implication that Gertz had a criminal record was false. Gertz had been a member and officer of the National Lawyers Guild some 15 years earlier, but there was no evidence that he or that organization had taken any part in planning the 1968 demonstrations in Chicago. There was also no basis for the charge that Gertz was a ‘Leninist’ or a ‘Communist-fronter.’ And he had never been a member of the ‘Marxist League for Industrial Democracy’ or the ‘Intercollegiate Socialist Society.’

*327 The managing editor of American Opinion made no effort to verify or substantiate the charges against Gertz. Instead, he appended an editorial introduction stating that the author (a regular contributor to the magazine) had ‘conducted extensive research into the Richard Nuccio Case.’ And he included in the article a photograph of Gertz and wrote the caption that appeared under it: ‘Elmer Gertz of Red Guild harasses Nuccio.’ The editor denied any knowledge of the falsity of the statements concerning Gertz and stated that he had relied on the author’s reputation and on his prior experience with the accuracy and authenticity of the author’s contributions to American Opinion. Welch placed the issue of American Opinion containing the article on sale at newsstands throughout the country and distributed reprints of the article on the streets of Chicago.

[Gertz] filed a diversity action for libel in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois. He claimed that the falsehoods published by [Welch] injured his reputation as a lawyer and a citizen. Before filing an answer, respondent moved to dismiss the complaint for failure to state a claim upon which relief could be granted, apparently on the ground that petitioner failed to allege special damages. But the court ruled that statements contained in the article constituted libel per se under Illinois law and that consequently Gertz need not plead special damages. 306 F. Supp. 310 (1969)

After answering the complaint, respondent filed a pretrial motion for summary judgment, claiming a constitutional privilege against liability for defamation. It asserted that petitioner was a public official or a public figure and that the article concerned an issue of public interest and concern. For these reasons, respondent argued, it was entitled to invoke the privilege enunciated in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254, 84 S. Ct. 710, 11 L.Ed.2d 686 (1964). Under this rule respondent would escape liability unless *328 petitioner could prove publication of defamatory falsehood ‘with ‘actual malice’—that is, with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.’ Id., at 279—280, 84 S. Ct., at 726. Respondent claimed that petitioner could not make such a showing and submitted a supporting affidavit by the magazine’s managing editor. The editor denied any knowledge of the falsity of the statements concerning petitioner and stated that he had relied on the author’s reputation and on his prior experience with the accuracy and authenticity of the author’s contributions to American Opinion.

The District Court denied respondent’s motion for summary judgment in a memorandum opinion of September 16, 1970. The court did not dispute respondent’s claim to the protection of the New York Times standard. Rather, it concluded that petitioner might overcome the constitutional privilege by making a factual showing sufficient to prove publication of defamatory falsehood in reckless disregard of the truth. During the course of the trial, however, it became clear that the trial court had not accepted all of respondent’s asserted grounds for applying the New York Times rule to this case. It thought that respondent’s claim to the protection of the constitutional privilege depended on the contention that petitioner was either a public official under the New York Times decision or a public figure under Curtis Publishing Co. v. Butts, 388 U.S. 130 (1967), apparently discounting the argument that a privilege would arise from the presence of a public issue.

After all the evidence had been presented but before submission of the case to the jury, the court ruled in effect that petitioner was neither a public official nor a public figure. It added that, if he were, the resulting application of the New York Times standard would require a directed verdict for respondent. Because some statements in the article constituted libel per se *329 under Illinois law, the court submitted the case to the jury under instructions that withdrew from its consideration all issues save the measure of damages. The jury awarded $50,000 to petitioner.

Following the jury verdict and on further reflection, the District Court concluded that the New York Times standard should govern this case even though petitioner was not a public official or public figure. It accepted respondent’s contention that that privilege protected discussion of any public issue without regard to the status of a person defamed therein. Accordingly, the court entered judgment for respondent notwithstanding the jury’s verdict.[18] [***]

Petitioner appealed to contest the applicability of the New York Times standard to this case. Although the Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit doubted the correctness of the District Court’s determination that petitioner was not a public figure, it did not overturn that finding.3 It agreed with the District Court that respondent could assert the constitutional privilege because the article concerned a matter of public interest… [***] After reviewing the record, the Court of Appeals endorsed the District Court’s conclusion that petitioner had failed to show by clear and *332 convincing evidence that respondent had acted with ‘actual malice’ as defined by New York Times. There was no evidence that the managing editor of American Opinion knew of the falsity of the accusations made in the article. In fact, he knew nothing about petitioner except what he learned from the article. The court correctly noted that mere proof of failure to investigate, without more, cannot establish reckless disregard for the truth. Rather, the publisher must act with a “high degree of awareness of . . . probable falsity.” [cc] The evidence in this case did not reveal that respondent had cause for such an awareness. The Court of Appeals therefore affirmed, 471 F.2d 801 (1972). For the reasons stated below, we reverse.

The principal issue in this case is whether a newspaper or broadcaster that publishes defamatory falsehoods about an individual who is neither a public official nor a public figure may claim a constitutional privilege against liability for the injury inflicted by those statements. [***]

Under the First Amendment there is no such thing as a false idea. However pernicious an opinion may seem, we depend for its correction not on the conscience of judges and juries but *340 on the competition of other ideas.[19] But there is no constitutional value in false statements of fact. Neither the intentional lie nor the careless error materially advances society’s interest in ‘uninhibited, robust, and wide-open’ debate on public issues. New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S., at 270. They belong to that category of utterances which ‘are no essential part of any exposition of ideas, and are of such slight social value as a step to truth that any benefit that may be derived from them is clearly outweighed by the social interest in order and morality.’ Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U.S. 568, 572 (1942).

Although the erroneous statement of fact is not worthy of constitutional protection, it is nevertheless inevitable in free debate. [***] And punishment of error runs the risk of inducing a cautious and restrictive exercise of the constitutionally guaranteed freedoms of speech and press. Our decisions recognize that a rule of strict liability that compels a publisher or broadcaster to guarantee the accuracy of his factual assertions may lead to intolerable self-censorship. Allowing the media to avoid liability only by proving the truth of all injurious statements does not accord adequate protection to First Amendment liberties. As the Court stated in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, supra, 376 U.S., at 279: ‘Allowance of the defense of truth, *341 with the burden of proving it on the defendant, does not mean that only false speech will be deterred.’ The First Amendment requires that we protect some falsehood in order to protect speech that matters.

The need to avoid self-censorship by the news media is, however, not the only societal value at issue. If it were, this Court would have embraced long ago the view that publishers and broadcasters enjoy an unconditional and indefeasible immunity from liability for defamation. [cc] Such a rule would, indeed, obviate the fear that the prospect of civil liability for injurious falsehood might dissuade a timorous press from the effective exercise of First Amendment freedoms. Yet absolute protection for the communications media requires a total sacrifice of the competing value served by the law of defamation. The legitimate state interest underlying the law of libel is the compensation of individuals for the harm inflicted on them by defamatory falsehood. We would not lightly require the State to abandon this purpose, for, as Mr. Justice Stewart has reminded us, the individual’s right to the protection of his own good name ‘reflects no more than our basic concept of the essential dignity and worth of every human being—a concept at the root of any decent system of ordered liberty.’ [***]