7 Intent

The intent level needed to satisfy most of the intentional tort action is an intent to act followed by the action itself. If an action is produced involuntarily (through a seizure, while sleeping or drugged against one’s will, for instance), the actor lacks the requisite intent. If an actor throws a ball at someone, hoping they will catch it, the intent to throw is the focus of the inquiry. Some courts have called this “purpose intent.” If the throw causes bruising when the ball accidentally hits the receiver’s face, it does not defeat the thrower’s intent even if the harm was unintended. Tort law calls the intent to cause the harm that happened (here, the facial bruising), “specific intent.” Specific intent is not required for most of the intentional torts and it is an error of law to confuse the standards; specific intent is higher than necessary for most intentional torts. (The exception is false imprisonment which requires proof of the specific intent to confine the plaintiff.)

Restatement (Third) of Torts: Liability for Physical and Emotional Harm

§ 1. Intent: A person acts with the intent to produce a consequence if:

(a) the person acts with the purpose of producing that consequence; or

(b) the person acts knowing that the consequence is substantially certain to result.

Villa v. Derouen Court of Appeal of Louisiana, Third Circuit (1993)

(614 So.2d 714)

This is an appeal by Eusebio Villa, plaintiff and appellant herein, from a jury verdict in favor of Michael Derouen, Villa’s co-employee, and Louisiana Farm Bureau Mutual Insurance Company, Derouen’s homeowner insurer, defendants and appellees herein. This case involves facts wherein an intentional act, by Derouen, i.e., the act of pointing a welding cutting torch in Villa’s direction and intentionally releasing oxygen or acetylene gas caused unintentional harm to Villa, i.e., second degree burns to Villa’s groin area.

After trial, the jury found that the defendant, Derouen, did not commit an intentional tort against Villa and, therefore, was not liable for Villa’s injuries. This finding of the jury foreclosed Villa from recovery in this action insofar as Villa is limited to worker’s compensation unless it was found that Derouen committed an intentional tort which caused Villa’s injuries.

Villa appeals contending that the jury erred in its finding that Derouen did not commit an intentional tort against Villa. We agree with Villa’s contentions and find that the jury clearly erred in finding that Derouen’s intentional act of spraying his welding torch in Villa’s direction did not constitute an intentional tort, specifically, a battery against Villa. As such, we reverse the judgment of the trial court and award damages accordingly.

This claim for damages arises out of an accident which occurred at M.A. Patout & Sons, Iberia Parish, Louisiana, on May 7, 1986. The evidence is undisputed that Eusebio Villa sustained burns to his crotch area and that these burns were caused by the actions of his co-employee, Michael Derouen. At the time of the accident, Villa was welding with a welding torch or welding whip. Derouen was standing to his left, using a cutting torch. Intending only horseplay, although one-sided, Derouen turned toward Villa and discharged his torch. Under cross-examination, Derouen responded affirmatively when asked if he placed the torch between Villa’s legs and also responded affirmatively when asked if he intended to spray Villa between the legs with oxygen when he placed the torch between Villa’s legs.

On direct examination, in response to questioning by his own attorney, Derouen qualified his previous answers, as follows:

“Mr. Lambert: … you did not have it in close proximity to his crotch?

Mr. Derouen: No.

Mr. Lambert: In fact, you did not even have it inside his body?

Mr. Derouen: No.

. . . . .

Mr. Lambert: When you squirted that, did you intend that that air actually cause him any pain, even minor pain?

Mr. Derouen: No.

Mr. Lambert: Did you intend that he even feel anything from the little bit of air?

Mr. Derouen: No.

Mr. Lambert: Why did you do it? What was your intention of doing that?

Mr. Derouen: To get his attention.”

Troy Mitchell, a co-employee, testified that a few minutes before the accident, he saw Derouen take his torch and blow pressurized oxygen behind Villa’s neck into Villa’s lowered face shield while Villa was welding. Mitchell testified that he told Derouen not to do that because it could ignite. Mitchell additionally testified that he thought Villa had also told Derouen to stop fooling around. Only a few minutes later, the accident which resulted in Villa’s burns occurred. Mitchell did not witness the accident because his welding hood was down at the time.

Marty Frederick, a co-employee of Villa’s, and Lambert Buteau, their supervisor, both testified that although they did not witness the incident, and could not remember Derouen’s exact words after the incident, *716 both understood that Derouen, in relating what had happened, was playing around with the cutting torch and “goosing” or trying to scare Villa at the time of the accident.

Derouen testified that he sprayed pressurized oxygen near plaintiff’s face prior to the accident. Villa testified that he felt the oxygen that Derouen blew on his face or head, heard Troy Mitchell telling Derouen to stop because Villa could be hurt, and made a remark himself to Derouen about it. Villa testified that, a few minutes later as he was welding with his face covered by his welding hood, he felt something blowing between his legs. He held still for a second, so as to not interrupt his welding, until he felt the pain in his groin area. He stated that, “I just grabbed with both of my hands. When I grabbed, it was a torch.” He continued by stating, “I grabbed in my private area where I feel the fire, and right there was the torch. I pushed it like that. It was Michael Derouen with the torch in his hand.”[1]

The fact that Villa reached down to his groin at the time of the injury, and either grabbed the torch or pushed it away, was undisputed at trial. It was also undisputed that, at the time of the accident, Villa was crouched welding with his welding hood down. The evidence revealed that while he was welding, due to the noise caused by the welding, Villa would not have heard Derouen’s torch aimed in his direction.

If an employee is injured as a result of an intentional act by a co-employee, LSA–R.S. 23:1032(B) allows him to pursue a tort remedy against that co-employee. In Bazley v. Tortorich, 397 So.2d 475 (La.1981), the Louisiana Supreme Court determined that “an intentional tort”, for the purpose of allowing an employee to go beyond the exclusive remedy of worker’s compensation, meant “the same as ‘intentional tort’ in reference to civil liability.”

A civil battery has been defined by the Louisiana Supreme Court in Caudle v. Betts, 512 So.2d 389, 391 (La.1987) as, “[a] harmful or offensive contact with a person, resulting from an act intended to cause the plaintiff to suffer such a contact….” (Citations omitted.) The Louisiana Supreme Court in Caudle, supra, at page 391, continued by stating: “The intention need not be malicious nor need it be an intention to inflict actual damage. It is sufficient if the actor intends to inflict either a harmful or offensive contact without the other’s consent. (Citations omitted.) ….

“The element of personal indignity involved always has been given considerable weight. Consequently, the defendant is liable not only for contacts that do actual physical harm, but also for those relatively trivial ones which are merely offensive and insulting. (Citations omitted.)

The intent with which tort liability is concerned is not necessarily a hostile intent, or a desire to do any harm. Restatement (Second) of Torts, American Law Institute § 13 (comment e) (1965). Rather it is an intent to bring about a result which will invade the interests of another in a way that the law forbids. The defendant may be liable although intending nothing more than a good-natured practical joke, or honestly believing that the act would not injure the plaintiff, or even though seeking the plaintiff’s own good.” (Citations omitted.)

Pursuant to this jurisprudence, we must determine whether Derouen committed a battery against Villa. Did Villa suffer an offensive contact which resulted from an act by Derouen which was intended to cause that offensive contact? Or as stated by Bazley, supra, at page 481, did Derouen entertain “a desire to bring about the consequences that followed”, or did Derouen believe “that the result was substantially *717 certain to follow”, thereby characterizing his act of spraying Villa as intentional?

There is a distinction between an intentional act which causes an intentional injury and an intentional act which causes an unintentional injury. To constitute a battery, Derouen need only intend that the oxygen he sprayed toward the plaintiff come into contact with Villa, or have the knowledge that this contact was substantially certain to occur.

The physical results or consequences which must be desired or known to a substantial certainty in order to rise to the level of an intentional tort, refer to the requirements of the particular intentional tort alleged. In this case, wherein Villa has alleged a battery, the harmful or offensive contact and not the resulting injury is the physical result which must be intended.

The record reveals that, although correctly instructed by the trial court, the jury appears to have been confused on this issue and, as such, manifestly erred, as a matter of law, in their verdict. The court instructed the jury as follows, as to the definition of the intentional tort of battery:

“In order for Eusebio Villa to recover from anyone in this case, he must first prove, by a preponderance of the evidence, that he was injured as a result of an intentional act. The meaning of intent in this context is that defendant either desired to bring about the physical results of his act, or believed that they were substantially certain to follow from what he did.

Eusebio Villa has alleged that Michael Derouen committed a battery upon him. A harmful or offensive contact with a person resulting from an act intending to cause the plaintiff to suffer such a contact is a battery. A battery in Louisiana law is an intentional act or tort.

The intention to commit the battery need not be malicious nor need it be an intention to inflict actual damage. The fact that it was done as a practical joke and did not intend to inflict actual damage does not render the actor immune. It is sufficient if the actor intends to inflict either a harmful or offensive contact without the other’s consent. It is an intent to bring about a result which will invade the interests of another in a way that the law forbids. . . . . .”

Although this definition was technically correct, several defense counsels, both in opening and closing statements, told the jury that, in order for them to find Derouen liable, they must find that Derouen intended to hurt Villa and/or intended to burn Villa. Additionally, the jury was misled by statements that their verdict in favor of Villa would make Derouen a criminal insofar as a battery was a crime.

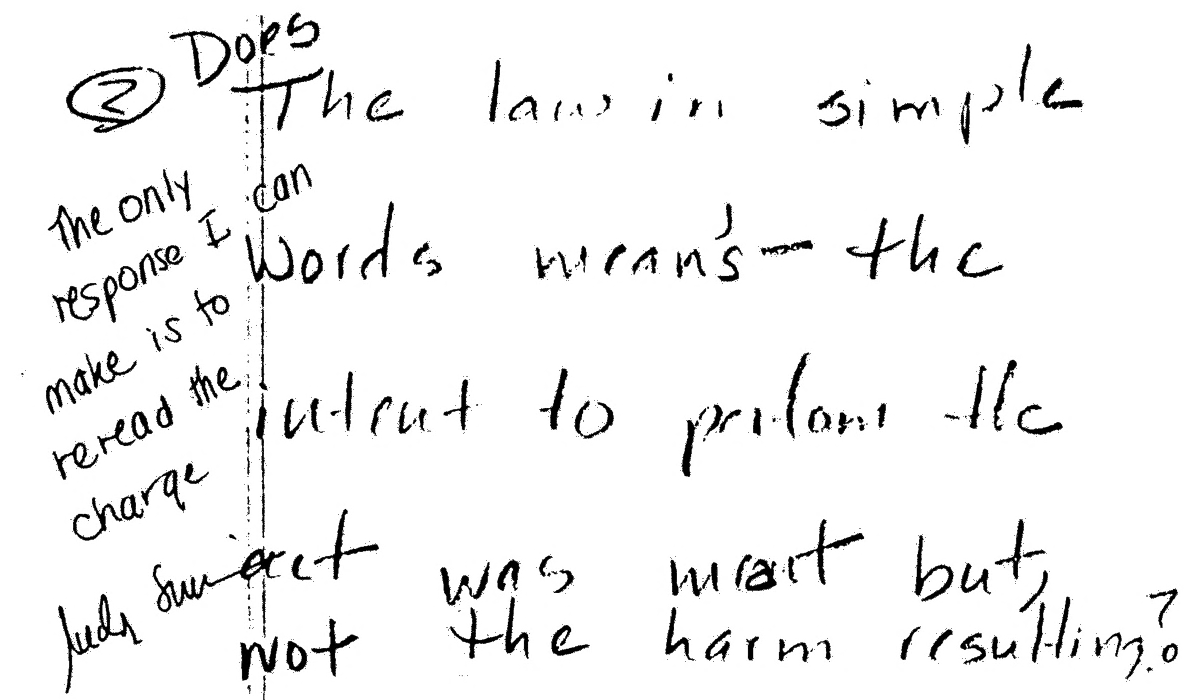

The jury voiced its confusion by sending a question to the judge asking him what the difference was between “an intentional tort and intentional (on purpose).” After the judge again instructed the jury with the charge set forth above, the jury sent out the query below [“Does the law in simple words means [sic] the intent to perform the act was meant but, not the harm resulting?”] to which the trial judge answered, as written [“The only response I can make is to reread the charge.”]: *718

Clearly the jury was confused as to whether they were to determine Derouen’s intent to perform the act or his intent to cause the resulting injuries. No clarifying instruction was given to the jury on this point of law. Had they understood the law, a reasonable juror could not have found that Derouen did not intend the act of directing compressed oxygen in the direction of Villa’s groin.

This distinction between an intentional act or unintentional act was recently highlighted in Lyons v. Airdyne Lafayette, Inc., 563 So.2d 260 (La.1990). In Lyons, an employee sued a co-employee alleging injuries as a result of the co-employee shooting a stream of compressed air at the plaintiff. The trial court granted summary judgment which was affirmed by this court. The Louisiana Supreme Court granted a writ of certiorari, and reversed the grant of summary judgment in favor of the defendant, stating as follows:

“There is a genuine issue of material fact whether plaintiff’s co-employee intentionally shot the stream of compressed air at plaintiff and injured him or whether the co-employee accidentally released the stream while repairing the compressor.” Id. at page 260.

Conversely, in the case at bar, there is no question as to whether or not Derouen intentionally shot the stream of compressed air at Villa.

This is not a case of an accidental release of pressurized oxygen or gas in Villa’s direction. Derouen testified that he did not intend, even the air he was pointing in Villa’s direction, to come into contact with Villa. It was unreasonable for the jury to accept that Derouen blew his torch at Villa, while Villa was welding and surrounded by the accompanying noise, in order to get Villa’s attention, but did not intend for Villa to feel the air directed at him.

In this case, Derouen intended to release the pressurized oxygen in Villa’s direction, at a minimum, to get Villa’s attention. Due to the noise, he would not have been able to get Villa’s attention unless Villa felt the air.

The facts are undisputed that Derouen aimed his welding torch and sprayed the pressurized oxygen or gas, which ignited, at Villa’s groin or at the ground between Villa’s legs. It is also undisputed that Villa was injured by the contact with the “flash” of Derouen’s welding torch.

*719 We find that the jury clearly erred in finding that a battery, i.e., an unconsented to offensive contact, had not occurred. The act or battery which Derouen intended was that of blasting pressurized oxygen or gas between Villa’s legs, into his groin area. Derouen testified that he merely wanted to get Villa’s attention. Due to the undisputed evidence that Villa was welding at the time of the injury, which welding was by its nature, accompanied by the noise of the welding, the defendant would not have approached Villa, expecting or intending him to “hear” the blast of air and thus, get his attention, without also expecting or intending Villa to “feel” the blast of pressurized oxygen and thus, get his attention.

Under the undisputed facts presented to the jury, we find that a reasonable juror could not have found that Derouen did not either intend for the air from his cutting torch to come into contact with Villa’s groin or, alternatively, we find that a reasonable juror could not have found that Derouen, in pointing his torch at Villa and releasing pressurized oxygen in the area of Villa’s groin, was not aware or substantially certain that the oxygen would come into contact with Villa’s groin area.

Villa sustained second degree burns to his penis, scrotum, and both thighs. He was first seen by Dr. James Falterman, Sr. on May 8, 1986, who hospitalized him from May 8, 1986, through May 16, 1986. Dr. Falterman testified that Villa was reasonably comfortable, with pain medication and treatment, within three (3) to four (4) days and, at a maximum, within one (1) week after the accident. Villa’s physical wounds healed completely, with some depigmentation, but no functional disability. He was discharged from treatment of his burns as of June 20, 1986.

Villa complained of being nervous and depressed on May 15, of 1986, and requested to see a psychiatrist. Villa was referred by Dr. Falterman to Dr. Warren Lowe, a clinical psychologist, who first saw Villa on June 9, 1986. Dr. Lowe diagnosed Villa as suffering from atypical anxiety disorder with depressive features together with some symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. At the time of trial, Dr. Lowe felt that Villa was getting better and was capable of entering a rehabilitation program.

[Editor’s note: The court ordered Derouen and his homeowner’s insurance company to pay $174,307.00. Module 6, on damages, revisits this case.]

The jury’s verdict finding that Michael Derouen did not commit an intentional tort is hereby reversed.

Note 1. Derouen testified that he did not intend for the air to make contact with Villa. How did the court dispose of that assertion? What did it say about the jury’s verdict with respect to this point? Which standard of intent does the court apply?

Note 2. For what purpose does the court cite Lyons v. Airdyne (*718), and what’s the deeper issue at stake?

Note 3. Transferred intent doctrine. Changing the facts of this case, if Mr. Derouen had intended to make contact with Mr. Jones, but accidentally hit Mr. Villa, the rules of intent would still have allowed Mr. Villa to bring a lawsuit. Under the doctrine of “transferred intent,” a defendant cannot escape liability by having the good luck to have bad aim. Indeed, the presumption is that had he hit Mr. Jones, Mr. Jones would have been the plaintiff instead. The doctrine, which has its origins in the writ system, has two aspects. First, if a defendant meets the requisite intent with respect to one person, but the effect of the conduct instead invades the interest of another, the required intent “transfers” from that intended person to the person actually wronged. Second, if a defendant meets the requisite intent for any of the core intentional torts (battery, assault, false imprisonment, trespass to chattels, or trespass to land), it can be transferred to satisfy the intent of any of the others. It does not apply to IIED (or to conversion, a tort related to personal property not covered in this casebook). In other words, the defendant does not escape liability by explaining that they merely meant to trespass on your property, but not to affect your chattels in anyway, or by explaining that they merely meant to frighten you into thinking they were about to harm, not to actually harm you, once they actually do commit a battery. If they meet the intent requirement for assault, it can be transferred to battery.

Note 4. Practice Stating the Rule. Notes and questions following assigned cases have focused thus far on formulating the legal question and holding but have not yet routinely asked you to formulate the “rule” of a case. Sometimes the rule is synonymous with the holding but often it’s not. The rule tends to be the principle for which the case will be cited (and there may be more than one rule, too). Discovering the rule requires skill that you will develop over time, as well as flexibility. Often the rule can be expressed in different ways, which may seem frustrating for those seeking a single correct answer, and sometimes the full scope of the rule will take subsequent cases to discern and develop fully. Recall how the holding in Davison altered slightly in Bartlett’s application of it, for example. Courts may later read a case for a certain proposition although that case never originally came out and announced its rule in that way. Consider how Guille v. Swan is now routinely understand as a paradigmatic strict liability case when at the time it was analyzed in terms of trespass. The rule as initially announced versus the rule as enduring principle that may eventually have lasting importance in the field can require some time to discern. This is why it is crucial to understand how rules evolve, how the facts and policies at play can both yield to and change rules over time. It helps lawyers to decode and predict the law, or at least to anticipate certain kinds of changes. That the rule can be expressed in different ways, or that multiple rules can exist does not relax the need for precision. Formulating the rule still requires precision. Practice stating the rule, or 1 or two 2 of the most significant rules you see in Villa.

Note 5. Note that the court raises Mr. Villa’s accent (and ethnicity) in its own footnote. Consider why it might have done so, and the possible effects on future courts and trials. Does the reference seem to hurt or help (and whom, and why)? According to the authors of a leading torts casebook, the court may have mentioned his ethnicity because Villa’s attorney, Charles L. Porter, believed that Villa was a victim of racial harassment. Villa, a Dominican man, was dating an African-American woman and his white Cajun fellow employees apparently found this objectionable and harassed him for it. “Villa’s attorney, now a state judge in Louisiana, raised this issue at trial, but the predominantly white, Cajun jury did not seem to respond well so he concentrated instead on the elements of the battery charge.” (Interview with Charles L. Porter, plaintiff’s attorney, July 18, 2001. Ibrahim J. Gassama, Lawrence C. Levine, Dominick Vetri and Joan E. Vogel, Tort Law and Practice, Fifth Edition (Carolina Press, 2016), p. 703.

The Restatement provided an additional way to define intent: knowledge, coupled with “substantial certainty” that consequences will follow. If you tossed a ball in the air near someone sleeping on the grass nearby and you knew “to a substantial certainty” that the consequence would be that the ball would strike that person, you intended to strike that person for the purposes of tort liability. In some cases, this distinction makes little difference, but in others it adds nuance that the court might find helpful or even dispositive. It is often easier to determine whether someone knew something (or could be expected to know something, because of their age or mental state or ability) than whether they intended something.

A classic mistake is finding no intent unless there is evidence of specific intent, which again means the intent to produce the harm that happened. After all, you could toss a ball at someone, fully intending to do that but imagining that your ball will land very lightly and be received in the spirit of good humor. But you could discover that your ball actually dealt a crushing blow and broke bones (perhaps because you were unaware of an underlying condition like brittle bones, or because you were genuinely unaware of your own strength). Nonetheless, for tort law, you intended to make contact and that is all that is needed. Trying to negate intent by explaining that you “didn’t intend to break anybody’s bones” will no good—that would be elevating the intent standard from intent to make contact to intent to bring about the harm that occurred from that contact. The former is the ordinary (or “purpose”) intent standard (intent to make contact) and the latter is “specific intent” which is not required (intent to produce the harm that occurred).

The next case provides an example of an application of the Restatement’s “knowledge to a substantial certainty.”

WMEL Water and Sewer Authority et al v. 3M, U.S. Dis. Ct. N.D. Ala. (2016)

(208 F. Supp.3d 1227)

The plaintiffs in this case are West Morgan-East Lawrence Water and Sewer Authority (the “Authority”), in its individual capacity, and Tommy Lindsey, Lanette Lindsey, and Larry Watkins (collectively “Representative Plaintiffs”), who bring this action both individually and on behalf of a class of persons similarly situated.[2] [***] The Authority and Representative Plaintiffs (collectively “Plaintiffs”) assert common law claims of negligence (Count I), nuisance (Count II), abatement of nuisance (Count III), trespass (Count IV), battery (Count V), and wantonness (Count VI) against 3M Company, Dyneon, L.L.C., and Daikin America, Inc. Currently before the court is 3M and Dyneon’s motion to dismiss the amended complaint pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6). [***]

This action arises out of defendants’ discharge of wastewaters containing perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), and related chemicals into the Tennessee River near Decatur, Alabama. Specifically, 3M and its wholly-owned subsidiary Dyneon own and operate manufacturing and disposal facilities in Decatur, which have released, and continue to release, PFOA, PFOS, and related chemicals into ground-and surface water, through which the chemicals are ultimately discharged into the Tennessee River. Daikin America manufactures tetrafluoroethylene and hexafluoropropylene fluoropolymers, produces PFOA as a byproduct, and discharges PFOA, PFOS, and related chemicals into the Decatur Utilities Wastewater Treatment Plant. The Wastewater Treatment Plant, in turn, discharges the wastewater into the Tennessee River.

*1232 Defendants discharge these chemicals thirteen miles upstream from the area where the Authority draws water that it supplies to local water utilities, or directly to consumers. Although the Authority treats the water, unsafe levels of PFOA and PFOS remain in the drinking water because of these chemicals’ stable carbon-fluorine bonds and resistance to environmental breakdown processes. Studies, including one by an independent science panel, have shown that absorption of these chemicals may cause long-term physiologic changes and damage to the blood, liver, kidneys, immune system, and other organs, and an increased risk of developing cancer, immunotoxicity, thyroid disease, ulcerative colitis, and high cholesterol.

Plaintiffs allege that defendants continue to discharge these chemicals into the Tennessee River despite knowing of the persistence and toxicity of PFOA and PFOS. Further, defendants are aware that tests of the Authority’s treated water have shown elevated levels of these chemicals. The Authority has consistently found PFOA levels at 0.1 ppb and PFOS levels at 0.19 ppb in its treated water, where 0.07 ppb is the current [Fn] EPA Health Advisory Level for both of those chemicals. As a result of these levels, the Authority has incurred costs of testing its treated water, implementing pilot programs to develop more effective methods for the removal of PFOA and PFOS, and attempting to locate a new water source.

Representative Plaintiffs and the proposed class are owners or possessors of property who consume water supplied by the Authority and other water utilities that receive water from the Authority. at 2. They allege personal injuries from their exposure to unsafe levels of PFOA and PFOS in their domestic water supplies, including elevated levels of those chemicals in their blood serum. In 2010, the federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (“ATSDR”) analyzed the blood serum of 121 customers of the Authority, including some of the Representative Plaintiffs and members of the proposed class, for PFOA and PFOS, and found an association between elevated levels of those chemicals and the use of drinking water supplied by the Authority. In addition to personal injuries, Representative Plaintiffs and the proposed class claim diminution in their real property values, and out-of-pocket costs for purchasing water filters and bottled water.

[***] E. Battery (Count V)

To state a claim for battery under Alabama law, a plaintiff must establish that: (1) the defendant touched the plaintiff; (2) the defendant intended to touch the plaintiff;[3] and (3) the touching was conducted in a harmful or offensive manner. [cc] Rest. (2d) of Torts § 18 (1965)). Representative Plaintiffs and the proposed class allege that defendants “touched or contacted” them “through their release of PFOA, PFOS, and related toxic chemicals” into plaintiffs’ water supply. Those plaintiffs further allege that defendants “knew that their intentional acts would be substantially certain to result in such contact,” and that such touching or contact “was and is harmful and offensive.”

1. Lack of physical injury

Defendants raise three arguments in support of their motion. First, they argue that plaintiffs have suffered no manifest physical injury. This contention is unavailing, because a claim for battery in Alabama does not require an actual injury to the body as an element of the claim. [cc]

2. Consent to the touching or contact

Second, defendants contend that dismissal is warranted because plaintiffs consented to the contact by voluntarily drinking the water. Plaintiffs claim that they did not “consent to their ingestion of and exposure to these toxic chemicals,” and, alternatively, allege that “consent is at most an affirmative defense to this claim that presents factual issues that cannot be resolved on a motion to dismiss.” [c] Indeed, it is apparent from the face of the amended complaint that Representative Plaintiffs and the proposed class use water filters or buy bottled water now, and once, voluntarily consumed the water prior to learning of the contamination. Thus, the question this court must resolve is whether the voluntary ingestion of water from the Authority (at least before they learned of the contamination) constitutes consent to the ingestion of the contaminants in the water. Because defendants failed to cite any Alabama law that suggests that plaintiffs’ consumption *1237 of the water constituted consent to their uninformed ingestion of PFOA and PFOS, the court will defer addressing this issue until the summary judgment stage.

3. Intent

Finally, defendants contend that dismissal is warranted on the battery claim because defendants did not specifically intend to touch or contact plaintiffs. Intent can be satisfied by substantial certainty [c] Plaintiffs allege that defendants are aware that they discharge PFOA and PFOS into the water, and that they know those chemicals appear at harmful levels in the treated water sold by the Authority. These facts are sufficient to give rise to a reasonable inference that defendants discharge PFOA and PFOS into the Tennessee River with substantial certainty that the water will be used for drinking and other household purposes.

For all these reasons, the motion to dismiss the battery claim is due to be denied.

[***] For the reasons stated above, 3M and Dyneon’s motion to dismiss is [***] as to …battery (Count V) [and other omitted] claims, and plaintiffs may proceed …, with the understanding that they may not pursue a private nuisance claim or negligence claims based on personal injuries. The court will reserve ruling on the sufficiency of the class allegations until a later date.

Note 1. Is the knowledge intent standard necessary to the battery claim on these facts? Could a purpose intent standard have worked as well? What sort of evidence do you think plaintiffs would need to show in proving either kind of intent? Is the difference one of kind or of degree?

Note 2. Tort law is one of the tools in environmental advocacy, whether it takes the shape of impact litigation, class actions or doctrinal developments to permit certain sorts of lawsuits. Professor Sanne Knudsen has written on the way that chemical latency could frustrate tort law’s causation requirement, for instance, and advocated the development of causation frameworks that can account for the complexities of what she has called “long-term torts” with significant ecological harms. Sanne H. Knudsen, The Long-Term Tort: In Search of a New Causation Framework for Natural Resources Damages. 108 Nw. U. L. Rev. 475 (2014), https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/faculty-articles/15/

Given what you know about the purposes of tort law and its capacities for change over time, does tort law seem like a good vehicle for achieving greater environmental justice? What do you imagine are the drawbacks, limits and costs of using tort law in this way?

Note 3. The court acknowledges that consent could defeat the plaintiffs’ claim because members of the class voluntarily drank polluted water; it will require resolution at a later date and this litigation is still unresolved. What do you think descriptively and normatively of this concept of consent?

Variations in Mental State

Another complexity in the determination of intent is that certain states of mind can negate intent though it’s not always intuitive which ones. Mental illness or disability does not negate intent so long as the defendant had the capacity to form the requisite intent (which is a question of fact for the jury). However, early case law is often not very nuanced in assessing mental states. Some cases may refer to people with mental illness or disabilities as “deficient” or abnormal or worse. It is worth paying attention to how advances in psychology make both the rhetoric and the substance of tort law more equitable over time. Being a child does not necessarily negate intent; the question will depend on how the jurisdiction treats youths and what we can determine about what they know.

Being drugged against one’s will most likely negates intent for everything that follows or a good deal of it, given that your powers of volition will be severely impaired. But being drunk does not negate intent. Nor does being mistaken about the facts; if you pick up a very lifelike-looking toy gun believing it to be a gun and try to shoot someone, your actions are no less culpable for the fact that you were mistaken about the status of the gun. This is different from bad aim or an intent to act that produces a different outcome from the particular one intended, which arose above in discussion of the doctrine of transferred intent. Transferred intent applies only to the intent necessary for five torts: battery, assault, false imprisonment, trespass to land and trespass to chattels.

Check Your Understanding (2-2)

Question 1. True or false: Genuine mistakes are often a means of negating intent for the purposes of finding an intentional tort.

Question 2. An epileptic has a sudden, violent seizure during church and, without warning, she knocks a smaller, frail individual seated next to her to the ground. He sues. What theory is likeliest to be most successful for him, and why?

Question 3. Which of the following facts, if true would most likely change the outcome of Villa v. Derouen (the pressurized oxygen coworker case)?

Classmate’s Kick Hypothetical: A twelve year-old boy, Abe, kicks another boy, Ed, while they are seated in their classroom. The kick makes contact with Ed’s kneecap which has, unbeknownst to Abe, a particular sensitivity. The kick causes intense damage and ensuing infection. Abe feels bad, but protests that he never intended this kick to hurt, and besides, he had no idea about Ed’s hidden condition. Abe’s father, who went to the same school as these young boys, and remembers fond games of tackle football with Ed’s father, says he is sure he has seen these boys wrestling on the playground before. How is this any different, he asks. He thinks that boys need to be able to engage in physical activity and roughhousing and this would be a ridiculous thing to sue over; can’t they laugh it off? Two surgeries later, Ed and his family aren’t laughing.

How would you use the rule you formulated in Villa to address this hypothetical? Or, if your rule(s) do not seem to govern this case, practice creating a new, descriptively accurate statement of law that analogizes or distinguishes this fact pattern from Villa.

Note 1. Eggshell Plaintiff or Thin Skull Plaintiff Doctrine. This hypothetical is loosely based on the facts of Vosburg v. Putney, a classic torts case which stands for several points of law (including on intent, context for conduct, and damages) (50 N.W. 403, Wis.) (1891). With respect to damages, it holds that just because the amount of harm was unexpected, the defendant is no less liable if their conduct otherwise satisfies the element of the tort. Sometimes known as the eggshell plaintiff or “thin skull” plaintiff doctrine, this principle predates Vosburg but is often cited in connection with it. The doctrine holds that the defendant “takes their plaintiff as they find them.” If a plaintiff has a thin, more easily injured skull, that may not be apparent to the defendant yet the defendant will still be liable for the extra damages this particular plaintiff suffers so long as the defendant’s conduct met the elements of the tort in question. Even if a plaintiff is extraordinarily susceptible to harm (they have brittle bones or for whatever reason the harm they suffer from the tortious conduct is worse than another plaintiff’s would have been), this doctrine makes it the defendant’s, not the plaintiff’s problem to resolve. Note that the eggshell doctrine does not only apply to pre-existing conditions; it can apply to a predisposition towards suffering worse harm or an unfortunately worse outcome. The standard for harm is thus not “objective” (what would a reasonable person’s injuries have been under the circumstances”) but “subjective” (what did this person actually suffer, on account of the defendant’s misconduct)?

In Smith v. Leech Brain & Co., 2 Q.B. 405 (1962), the plaintiff, William Smith, was injured at work when his employer failed to provide adequate safeguards to prevent injury in the presence of molten metal. Smith sustained a serious burn on his lip from a spattering of molten metal, and while only the lip was burned, the wound failed to heal. Smith eventually developed cancer at the point of the burn which caused his death. His wife sued for damages and won. The court rejected the defendant’s arguments that the damages suffered were out of proportion to the harm by the defendant. Though that was a negligence case, it illustrates the application (in all domains of tort law) of the eggshell plaintiff rule.

Note 2. One scholar explores the use of the eggshell plaintiff doctrine to deal with pre-existing conditions that are not created by new tortious conduct but significantly worsened by it. Dean Camille Nelson analyzes when courts have used the doctrine in service of corrective justice, and considers its analogous use to redress harms to women and people of color for whom pre-existing traumas or particular conditions might be triggered or worsened by tortious conduct:

“The extent to which the Thin skull doctrine has been stretched is evidenced by the case of Warren v. Scruttons Ltd.[4] The plaintiff had a pre-existing ulcer on his left eye when he cut his finger on a wire on the defendant’s equipment. The wire apparently had a type of chemical on it, described as “poison,” which led the plaintiff to contract a fever and a virus. This resulted in further ulceration of the eye. The defendant was found liable and the court held that, “any consequence which results because the particular individual has some peculiarity is a consequence for which the tortfeasor is liable.”[5] In terms of equality arguments,[6] women have been compensated for injuries specific to our sex. For instance, the Thin skull doctrine has been applied to compensate pregnant women who have suffered miscarriages or who have had stillborn children.[7] Similarly, where a woman whose ovaries were weakened by a previous operation suffered injury as a result of a sudden stoppage of a train, the court granted recovery on the basis that “the weak will suffer more than the strong.”[8] If sex does not present a bar to recovery based upon particular vulnerabilities, why should race? Race-related, or racism-related mental disorders, might similarly be infused into the Thin-skull doctrine as it has generally allowed for recovery based upon such mental vulnerabilities. Alternatively, this might more properly justify consideration of the Eggshell personality doctrine. If a physical injury triggers mental suffering or nervous disorders, the defendant must pay the resultant damages, even if they are more serious than might be expected.[9] If, however, there is a pre-existing mental condition rendering the plaintiff particularly vulnerable, courts may still allow recovery, thus transforming the thin-skull plaintiff into one a plaintiff with an eggshell personality.

Camille A. Nelson, Considering Tortious Racism, 9 DePaul J. Health Care L. 905, 960–61 (2005)

Note 3. Having read about the eggshell plaintiff and begun to consider its possible extensions and limits, revisit your understanding of intent. Might it make sense to apply the eggshell plaintiff doctrine only in cases in which there was a particular intent level, such as specific intent to harm? What is the effect of its applicability to not just intentional torts but negligence? Which of tort law’s purposes is most apparently driving the robust application of this doctrine?

Check Your Understanding (2-3)

Question 1. Which of the following statements is true of the eggshell plaintiff doctrine:

Expand On Your Understanding – Intent Hypotheticals

Review the following hypotheticals, which feature various forms of violence to the body as a means of testing the scope of the intent requirement. The questions are designed both to test some of the rules you already know as well as to add to your understanding. Do not feel too concerned if you are learning some rules for the first time in addition to testing and reaffirming some rules you have already learned. Turn each card to reveal the answer.

- Mr. Villa is a Puerto Rican native who came to the United States for the first time in 1973 and has a strong Spanish accent. ↵

- The proposed class consists of “all owners and possessors of property who use water provided by the West Morgan-East Lawrence Water and Sewer Authority, the V.A.W. Water System, the Falkville Water Works, the Trinity Water Works, the Town Creek Water System, and the West Lawrence Water Cooperative.” ↵

- A plaintiff can establish “intent” by showing that the defendant “desires or is substantially certain of the injury to result from his or her act.” [c] ↵

- Warren v. Scruttons Ltd., (1962) 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 497 (Q.B.D.). ↵

- Id. at 502. ↵

- See Dennis Klimchuk, Causation, Thin Skulls and Equality, 11 Can. J.L. & Juris. 115 (1998) (advocating for the entrenchment of tort-like Thin skull principles in criminal law). Where, for instance, a victim is stabbed, looses [sic] a significant amount of blood, denies a blood transfusion on religious grounds and dies, Klimchuk states that the thin-skull rule should allow for the finding of proximate cause –to do otherwise would violate principles of equality. The defendant should be found culpable for the death of the victim. ↵

- Malone v. Monongahela Valley Traction, 104 Va. 417 (1927); Schafer v. Hoffman, 831 P.2d 897 (1992). ↵

- Linklater v. Minister for Railways, [1900] 18 N.Z.L.R. 526, 540. ↵

- Linden, supra note 236, at 330. Linden points out that in a case involving the claim for mental suffering by a plaintiff as a result of being thrown against a seat of a streetcar when it collided with a train, the Supreme Court of Canada recognized that the “nervous system is as much a part of a man’s physical being as muscular or other parts.” Toronto Railway Co. v. Toms, 44 S.C.R. 268, 276 (1911). Vargas v. John Labatt Ltd., [1956] O.R. 1007. ↵